In Trusting in God

By Mamoun Altalib

This act seems entirely foolish in a capitalist state and system, let alone in Sudan, during the era of a religious police state. Sudanese people have been guided by this strange jurisprudence alien to the modern world, to the extent that you might think they are either prophets or fools in such situations. Therefore, it appears that most exploiters of war conditions are strangers.

The morals left by the Muslim Brotherhood have become apparent and contradict the morals of Sudanese people, all across its territory. They raised rents, transportation costs, and the cost of living itself.

You cannot trust in God while banks, markets, free trade, and the corrupt system still rule the day, like a drug addict filling his veins.

But in times of war? No one to trust but God.

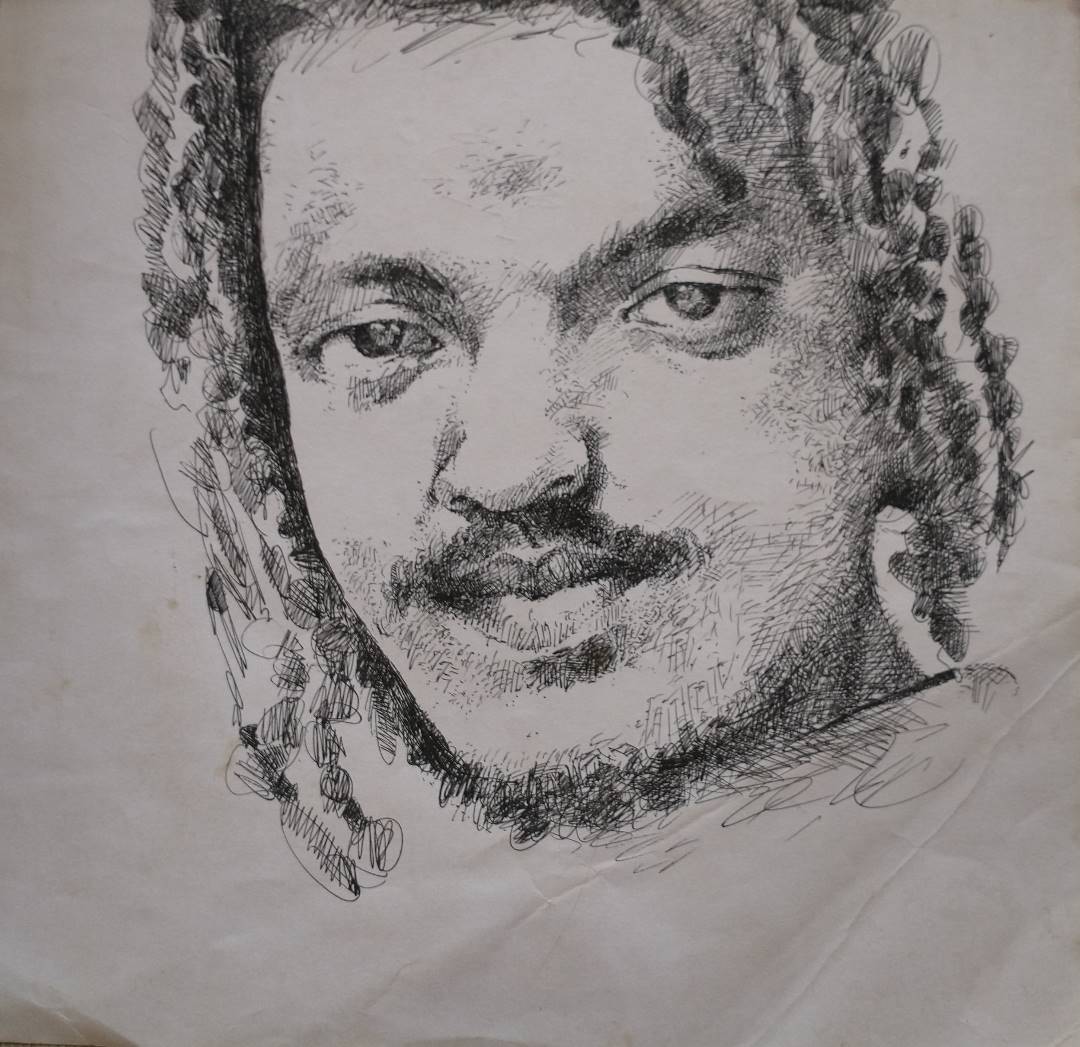

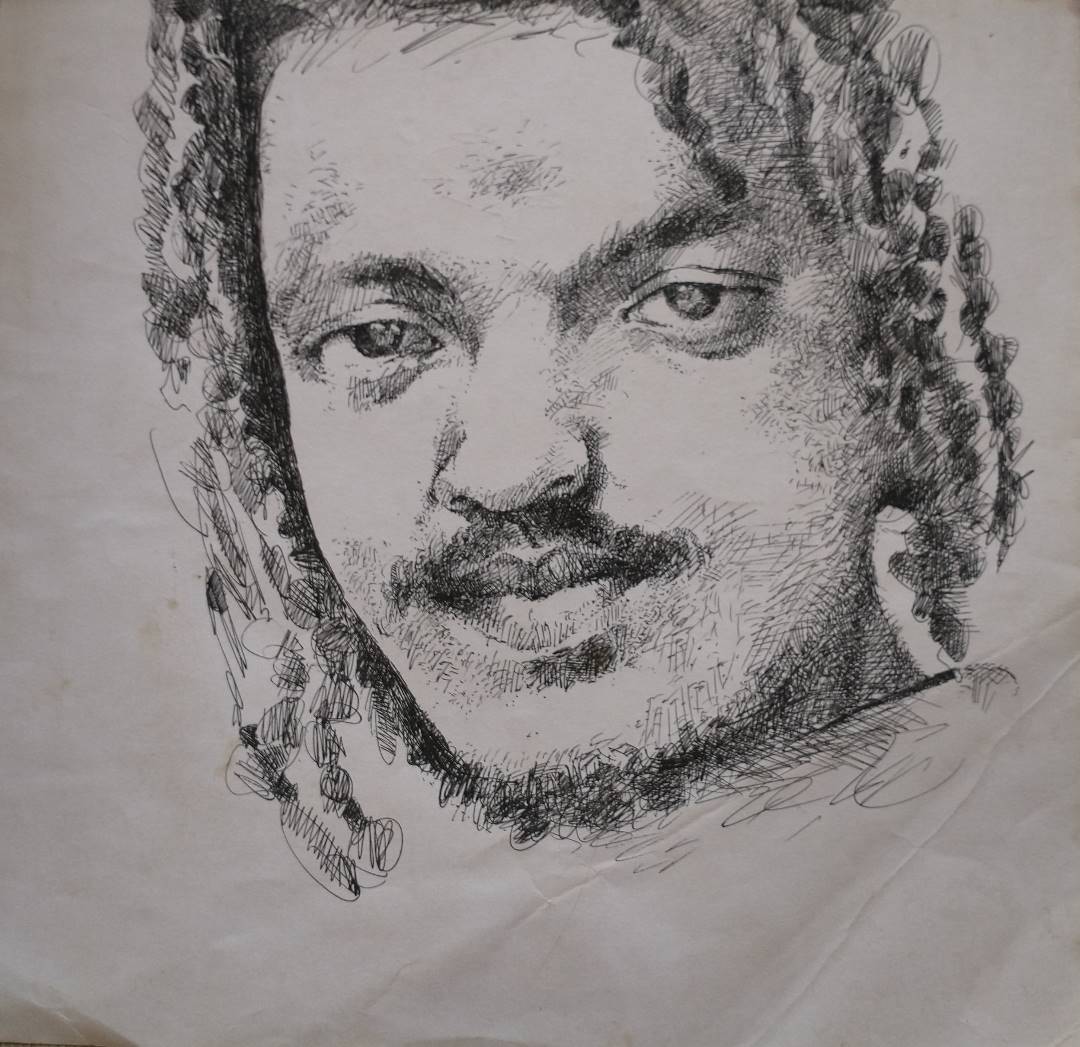

It is the Lord whose immense power you can only feel in situations like these, as artist Abdullah Mohamed At-Tayib described: Nylon bags floating in the air, not knowing where, when, and why!

Indeed, everything has become plastic in a horrifying way, and trusting in God has become foolish. But what led to mockery and ridicule of our absurd condition other than this trust? My friend, Namaa, who spent her final days in Khartoum amid battles in Jebel Awlia, being evicted from homes, said, People misunderstand the situation completely. They trust in God and hope the plane will hit their roof? By God, our Lord saves us, but He tells you, You take the first step, and I will save you.

Now, what does survival really mean? For me, its meaning has become misleading in a sarcastic manner. While we have lost unpaid jobs that barely cover housing, food, and drink expenses, we find ourselves in a fossilized capitalist world.

In the past, we had goals. Our work was purposeful: liberating a magazine, or cultural pages, a noble endeavor, as taught by Osama Abbas and Saddig El-Raddi. Even if it didnt provide financial returns. But we also learned that such work couldnt be noble outside the Niles lands, its deserts, and its forests. What are we really trying to change? The world? The terrible global system? At least, the geographical context we were in meant something called a homeland, and people sacrificed for it. But who do we sacrifice for now? And why? You are just a nylon bag floating in the air.

As we entered the modern era during the war, we found we didnt even know how to get jobs or make money! True, many of the expatriate writers and artists regretted leaving after the rescuers saved us, but they are now in a better situation, having understood and experienced how to manage their lives within the heart and arteries of the fossilized world. But we, who trusted our God, were saved by Him but confronted with another unknown God: The God of Small Things, as Arundhati Roy puts it, the one who only sees in you flesh to be dissected in painstaking detail.

Today, I live in a small village of about 300 people a year. High up in the mountains in southwestern Uganda, it sits beneath a whole lake, which is part of the sources of Lake Victoria. At this moment, as I write, I sit atop the origin of the White Nile. They wake up at dawn and head to the fields, returning during the day and heading straight to the halwah huts, where they slowly drink small cups of banana brew and laugh—men and women of all ages, and their children running around. Mountains and rain, even the clouds personally pass through our house every morning. As I write now, the rain fills the water tanks and nourishes the soil of our land with the eagerness of birth and beauty. With all this, I lost faith, or rather, I lost everything.

No beauty in the world can compare to the beauty of our city, Khartoum, the beauty of its people and their harsh struggle for a better life. How much we wept over the iron bars of the Blue Nile Bridge facing the Armed Forces, while we watched millions of Sudanese people raise their phones and sing their anthem. Even Wad El Zain, the biggest pessimist, was sitting beside us, me and Afifi, and he was optimistic.

I want to say that I hated my city, Omdurman, for its superiority over Sudanese people, and I hated Khartoum more, and I did everything in my power to prove its arrogance and bragging. But today, I sympathize with myself and say, as the angel says: Your youth, what did you spend it on? How did you spend your life fighting Khartoum?

I remember now the days we were rejected by the newspapers and turned into mere proofreaders in the laboratories, which we call slaughterhouses, with our designer friends. After the evening shifts starting at four and ending at ten, I used to walk from Sharia Almakk Nimir up to the modern bridge, passing by Beit Asha, where you have a qazzaza of your liquor, and then your mind dives into the Nile. You sit and stretch your legs, and also on the riverbanks nearby, where the bridges pillars are, you see children sleeping without cover, sleeping deeply. Youll never know how they feel or what they dream, until your war comes: where daily nightmares become normality you wont even tell your wife about, because youll become boring and sick.

Finally, I redefine myself: I am an ancient Khartoumi, and I will never give up on my city. If I die, tell it that I loved it, and I will not love any other city.

2nd August 2023