On the 20th Anniversary of Edward Saids Passing

Dying Youth: Edward Said and the Power of Adornos Despair

By Michael Wood

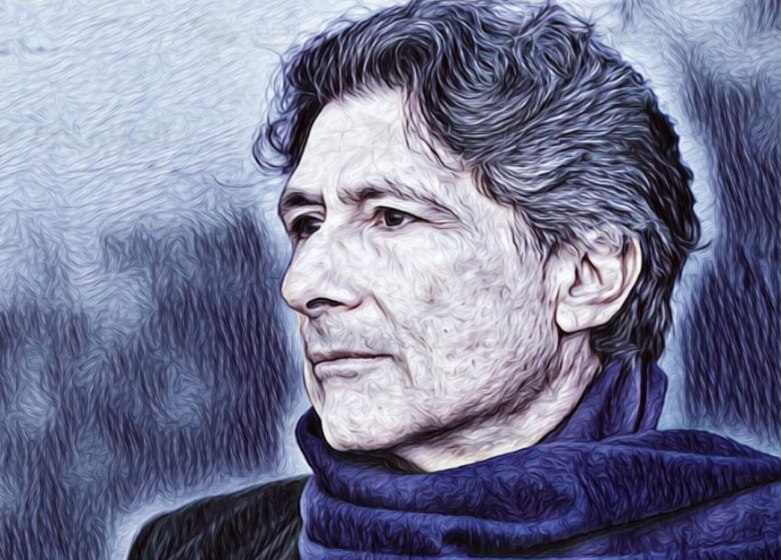

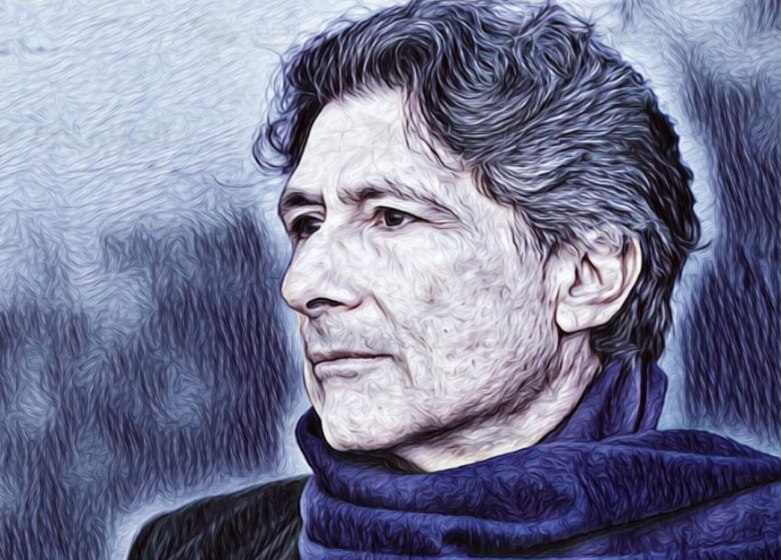

A month or so after Edward Saids passing, I came across some documentary photographs that seemed recently taken but strangely familiar to me. These images didnt add anything to the mental pictures I already had: Edward Said sitting at his desk, peering through his glasses at what lay around him, looking pensive and stern, looking distracted and serious, with a thin beard and sunken eyes, appearing like a sage who had endured long fasting. He seemed vigorous and active, just a bit tired.

In most of these pictures, Said was wearing a jacket and tie (the image of an intellectual) and he seemed to be fully engaged, meeting an unending stream of people. Even the image of that child, who was Edward and graced the cover of his book Out of Place, showing him secluded and dignified, his thoughts in constant turmoil, seemed oddly familiar to me.

So what Im talking about is not – by any means – a transition from one look to another over time.

Then one day, I watched a short film featuring Edward Said and Salman Rushdie, among others, in a debate at Columbia University, I believe. The assembled footage was somewhat dated, probably from the mid-1980s. However, in these shots, Edward appeared to me as if he were dying in his youth, which left me utterly bewildered and in a desperate quandary. He looked as though he were dying a second death!

What happened, and what compelled me to say he was dying in his youth?

I think there are multiple and somewhat different elements that started coming into play.

One reason that led me to say this, despite my ongoing contemplation of Edward over the months and months that followed since I first knew him in 1964, almost forty years ago, is that Edward meant for me more of a voice and a physical presence, an energy source, a friendship, and more thoughts than an image.

I felt him and heard him more than I saw him. Or maybe I saw him, but I saw in him that hidden, vibrant self that we attribute to people we know and love as we journey through lifes paths.

Another reason is the media that deliver these films and photographs to us. Films and photographs, both, are forms of memory, but they lack the gentleness and continuity of pure mental style.

Films and photographs harshly evoke the moments, the dress code, the gestures, and the poses; what Louis Pauwels calls the natural geography of faces. They date the details as if they were time-stamped records working for time itself.

Images and films do not just say: This happened, as Roland Barthes states about photographs, and they do not just say: This person was there, but they say: This person, at this very moment, is the same person and no one else. But we might also need to distinguish between still images and moving images.

A photographic image is a certificate of presence, as Roland Barthes says, and its message is that this person who fell prey to the instant of photography will never return to this instant and will eventually die.

The cinematic image delivers the same message but in a more poignant manner. Movement is the essence of life, Pauline Kael declared, even though she was busy at the time trying to freeze movement so she could see how it worked. Because the cinematic image moves, it confirms not only the active existence of life but also pure human existence that continues to live quantitatively and qualitatively, oblivious to death. Hence, films seem like sacred immortality and processions of beings that once were and cannot die.

But none of this takes us beyond the fact of the film showing Said and Salman Rushdie. This is part of the shock I am experiencing, and there is more to what I saw in that film and what Ive recently seen in various other films representing different stages of Edward Saids life. Its not just (the past), and its not just instances of Edwards changing life, and its not something that reminds me of time, for I havent forgotten time and its changes; perhaps Ive just forgotten the details.

What I saw in that film were human forms moving in a meeting filled with all thats hidden. Yet, human intuition can capture all this hiddenness and the historical moment to intensify it, as well as to capture what brought Edward and Salman Rushdie together from Egypt, India, America, and England. Human intuition can also capture what differentiates them.

The past rushes toward the present and throws itself into its arms, but the cinematic image is full of what has not happened yet, or perhaps it was hidden from my sight by that being I knew what would happen to.

Not everything that recently happened to Edward was dreadful, but some of it was. He suffered politically and personally.

Edward was fond of quoting from Theodor Adornos themes about modern music. He would quote lines like, The message of despair clinging to life often arises from shipwrecks. Edward witnessed several shipwrecks, especially the political ones, and acknowledged the power of Adornos despair, but he acknowledged it to move forward.

Edward Saids works and his life call on us primarily to think not about fading youth or vanishing potentials, but about the determination to hold on to hope despite the vicissitudes of time. We die and grow old when we lose hope. We all do that at times, but when we lose the idea of hope, we lose the opportunity to bring it back.

Michael Wood is a university professor and an American critic.