Sudan in Letters and Blogs: January 1918 - January 2018

Dr. Ahmed Sadiq Ahmed*

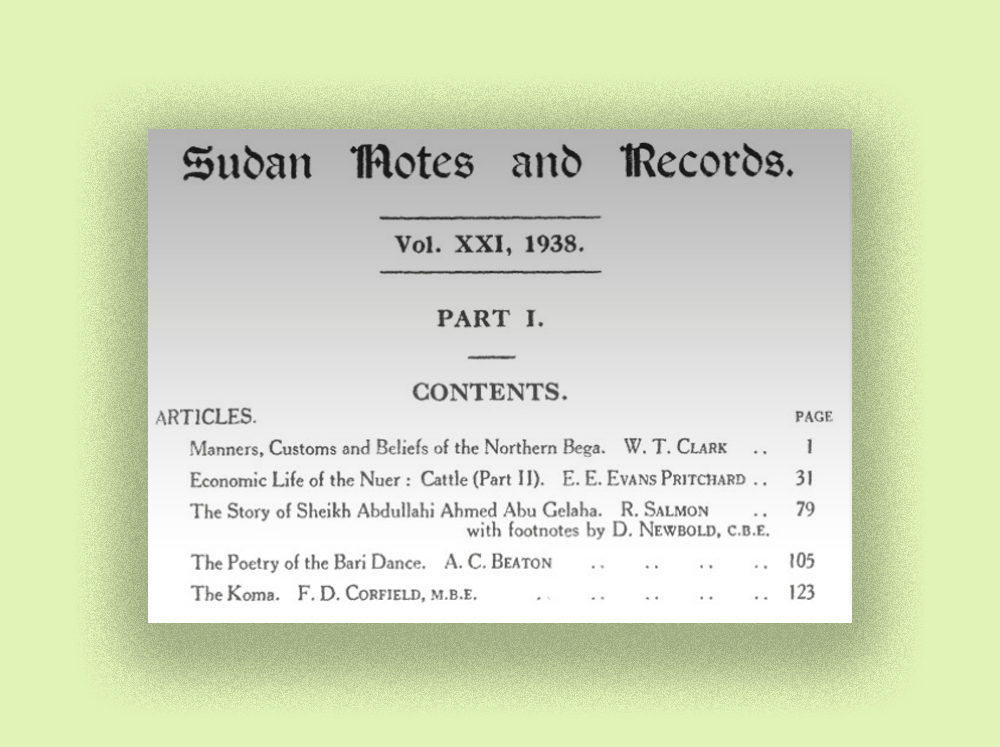

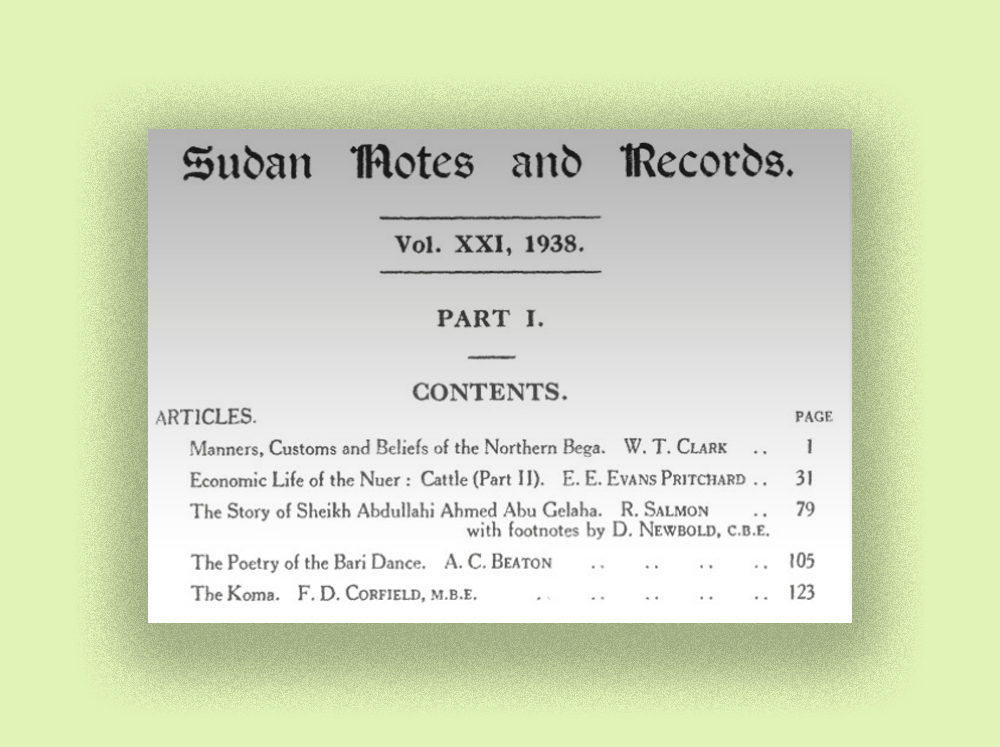

Since the release of the first issue of the journal Sudan in Letters and Blogs, as proposed by the late Abdullah al-Tayeb for Sudan Notes and Records, or as it is referred to in the research texts, SNR, it could have celebrated its centenary had it not ceased publication in 2005.

The first issue of the first volume was published in January 1918 and was inaugurated by the words of Sir Reginald Wingate or Wingate Pasha as he later became known in literary circles, the Governor-General of Sudan (1900-1916). He began by saying, ... I am delighted to see the publication of this scholarly journal, especially given Sudan, the fertile land, abounds with myths and stories, particularly from non-Arab and non-Muslim ethnic groups. This is of anthropological significance for understanding these people, their values, and prevailing ethics, which is very important for those managing the affairs of these peoples.

The editorial board persevered in issuing one volume after another, achieving unparalleled success for over eight decades, particularly within scientific circles around the world. This was because, for historical and objective reasons, it adopted the English language, which has remained the primary means of communication to this day.

The scene was opened with five articles that realized the colonial dream, as suggested by the British colonial engineer Wingate Pasha, of achieving a policy that satisfied their colonial desires by increasing their knowledge of the peoples who fell under the empire.

The initial study about the history of ancient Sudan was written by Raisner, who became renowned for his archaeological discoveries and writings about the Stone Ages in Sudan. He did not cease to delve into Sudans history and later contributed several studies in this regard. This was followed by a study by Mr. S.H. Stigand on the sight and smell of animals. Then there was an early brief study about the Sakia in Dunqula written by Nicholas.

However, the most significant study in our opinion, within the context of launching the journal, was conducted by the Arabist Hilalson, who had long shown a special interest in the Arabic language of the people of Sudan in all its dialects, hybrid forms, and its fusion with local languages to the extent that it manifested in the vocabulary, structures, and sounds of the Arabic language mingled with Sudanese languages. He focused in his first article published here, which received the lions share of writing in the same field, on the Sudanese Arabic language in its most evident form. This is the Arabic language of the people of Sudan, which expanded with all its idiosyncrasies, as he put it, due to the influence of local languages – tribal languages, as mentioned in the colonial context. It is worth noting here that in the bibliography compiled by the late Nasri (1982) about Sudan in Letters and Blogs, it was mentioned that Hilalson took the lions share in terms of the number of studies he wrote, all of which revolved around the Sudanese language and what he revealed about it in terms of identity, memory, and history.

How beautiful is that colonial Jew in his early studies here, when he wrote about what he called folk songs, specifically those sung by children:

O tree climber,

Bring me a cow,

Milk and feed me.

And also,

O those who lift me, come and feed me.

This reflects his clear interest in the heritage carried by the Arabs of Sudan, here and there in time. How could he not, as he was the first to draw attention to the book of classes by the poor Muhammad al-Nur Wad Diif Allah? More importantly, it was he who drew the attention of Sheikh Babiker Badri to the strength of Sudanese proverbs, the necessity of collecting them, studying them, publishing them. He included many of them in his two books, Arabic Texts from Sudan and Arabic Vocabulary of Sudan, both published in 1922 and 1927. Its worth noting that the first book coincided with Sheikh Abdullah Abdul Rahman al-Dires book, Arabic in Sudan. In addition to this, he mentioned stories, sayings, and proverbs from Sheikh Farah Wad Tiktok Swar al-Mashbouk, which he had a pioneering role in narrating.

The conversation continues and branches out, and it becomes more complex when it comes to the presence, diversity, and multiplicity of Hillesons writings in this context.

The last article was written by one of the icons of colonial writing, Sir Harold MacMichael, about some aspects of Nubian culture in Darfur. Its worth noting that his project about Arabs of Sudan began in this context and concluded with his well-known book by the same title, which was first published in two volumes in 1922 and later translated into Arabic. After a few intriguing references to the origin of treasures and their mixing with the Nubians in southern Aswan, the migration of the Rabia tribe, and his claim that they abandoned their Arabic language and merged it with the Nubian language, he claimed the end of the kingdom of Dongola and the beginning of the domination of Jahina - a group of Qahtani Arabs from the Hijaz. He concluded by presenting a detailed overview of the situation in northern and southern Darfur. After that, he explained how some elements of the Nubian language and culture seeped in and settled in Darfur due to the long period of interaction between different groups in Darfur and Mali. All of this is manifested in the Nubian elements of customs, traditions, words, structures, and expressions within different ethnic groups in Darfur.

The editorial boards statement in the last pages should be noted: After praising Mr. Wingate Pasha for his support and encouragement of the magazine project and his contribution to the export referred to earlier, they highlighted the difficulties they faced in printing it in Britain due to the circumstances of the post-World War I period. However, they managed to print it in Cairo with generous assistance from the French mission. One of the most important points in their statement is their stern language regarding the future of the magazine and who will write for it. They emphasized the importance of focusing on the Sudanese heritage in all its aspects, including history, archaeology, folklore, governance systems, and administration, in line with the policies they set for the magazine.

In conclusion, this issue included a comprehensive presentation of most of the research and studies published in international journals that focused on Sudan. The latest presentation was a scientific study about the types of butterflies in the Nuba Mountains.

Finally, the issue included several letters. The first was from the Blue Nile Directorate, which claimed to have found in the pocket of Mohamed Ahmed El Sadig, one of the associates of Wad Haboba, who was accused of killing Mr. Moncrieff. I do not know the reason for including this document, if we consider it a document at all. The second letter was from the Khartoum Directorate, this time about elements of Christian heritage in some urban areas, despite the fact that Christianity had completely ended more than four decades prior, as claimed by the writer when the kingdoms of Soba and Alwa came to an end.

The issue also included a few advertisements from Gillat Brothers, the Egyptian British Bank, and the Bank of Egypt. The price of the issue was three piasters, and the annual subscription was fifty piasters.

Since this text (the magazine) was produced in a colonial context, the magazine and its contents inevitably become part of colonial heritage and legacy, at least until the decolonization process. This is a critical perspective in principle, with a contextual reading. However, upon reviewing the periodical and its contents, we find that it carried a purely Sudanese heritage, perhaps even national? Generations and generations will refer to it as a significant achievement in this complex geopolitical context. Of course, after stripping it of the stains of colonial authority or the pathologies of colonial discourse, as the late Edward Said put it, this does not mean at all that the magazine has been distorted or damaged by colonialism. Much of it was just filler content with no relevance to science or human knowledge, nor to Sudan or its people.

At the same time, many excellent articles adorned the pages of this magazine. An important note here is what Al-Hashimi accomplished by translating a considerable number of them. He deserves respect and admiration.

We cannot overlook important knowledge moments during the more than eighty years in which this periodical appeared. For instance, what Kirk (1944) wrote about Sudanese orchids in Mexico. It was one of the early writings that followed what Prince Omar Tousoun (1933) wrote, or rather, no one wrote about it before him. You can find many valuable writings, starting with Ibrahim Badri and passing through Abdullah El Tayeb, Nasr El Haj Ali, and even Salah El Mazri, for example, and the list goes on. For years after independence, it was published by the Office of the Governor-General, as well as the Philosophical Society, and it ended with its publication by the Institute of Asian and African Studies at the University of Khartoum.

The raw materials of the periodical are still waiting for further research, analysis, and perhaps editing and reissuing in a new format, as has happened before. Some scattered issues are still available at the bookstores of the Institute of Asian and African Studies. The complete collection (original and reprints) is available in the Netherlands at the prestigious Brill Publishers. However, what is more important than all of this is digitizing it so that it becomes accessible to researchers on electronic platforms, not just individuals but also institutions.

*Academic and Sudanese writer (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia).