Traditional Justice and Reconciliation after Conflicts in Africa 5-5

Luc Huyse

International instances

Where a brutal conflict has crossed borders the odds are that transitional justice policy will also have international ramifications. Charles Taylor, a Liberian and key perpetrator in the Sierra Leone civil war, had to stand trial in Freetown. (He was transferred to a tribunal in The Hague, the Netherlands, for security reasons.) In other cases a legacy of violence is internationalized because foreign countries or the UN have taken up the role of peacemaking facilitator. This happened in Burundi. As a consequence national justice and reconciliation strategies were developed according to internationally inspired models. Finally, there is the influence of international law. Its insistence on the duty to prosecute may restrict the policy choices national authorities can make. This is currently a major point of discussion in northern Uganda. Such pressure has been growing over time. When the civil war in Mozambique came to an end in 1992 an amnesty act passed without international protest. That would no longer be the case today.

Civil society

All the authors of the case studies in this book put clear emphasis on the important part civil society has had, still has or might have in dealing with the grisly fallout from their country’s wars. Local NGOs, separately and/or through networking, try to influence the decision-making processes of national and international authorities. The majority of the churches in Gorongosa (Mozambique) totally discouraged ideas about achieving retributive justice. The Inter-Religious Council of Sierra Leone was involved in some of the hearings of the TRC. The National Council of Bashingantahe in Burundi has lobbied for inclusion and involvement in the post-war policies of the government. Victims’ associations in Rwanda pressure the authorities in questions of accountability and reparation. The Northern Uganda Peace Initiative (NUPI), a network of associations, has strongly supported the use of mato oput and cleansing ceremonies. Other local NGOs in the region, however, are fighting for criminal prosecutions. Opinions thus diverge. Such variety in viewpoints is not an exception. It is an important feature of civil society in most post-conflict countries.

International NGOs such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are not absent in the debate on transitional justice policies. In the course of their vigorous lobbying for an effective ICC and for the extension of universal jurisdiction they have tended to put a robust emphasis on retributive justice. Doubts about the justification of traditional practices abound.

Culture

No Future Without Forgiveness is the title of Desmond Tutu’s personal memoir of chairing the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He argues that the conditional amnesty the TRC could grant was ‘consistent with a central feature of the African Weltanschauung (or world-view)—what we know as ubuntu in the Nguni group of languages, or botho in the Sotho languages. … A person with ubuntu is open and available to others, affirming of others, does not feel threatened that others are able and good; for he or she has a proper self-assurance that comes from knowing that he or she belongs in a greater whole’ (Tutu 1999: 34–5). It is this fundamental attitude that opens the heart for forgiveness. This is mostly closely related to religious convictions. In their case study on Mozambique, Victor Igreja and Beatrice Dias-Lambranca write: ‘Christian religious groups in Gorongosa rely entirely on unilateral forgiveness since God is considered to be the most important figure in the resolution of conflicts’. On the other hand, the practice of forgiving and forgetting may be widespread in Africa but it is not a general cultural given. The results of two surveys on peace and justice in northern Uganda were released in August 2007. One was conducted by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), with the participation of 1,725 victims of the conflict in 69 focus groups in the Acholiland, Lango and Teso sub-regions, and with 39 key informants to provide a degree of cultural interpretation of responses from the focus groups. The report concludes that perceptions on the virtues of amnesty, domestic prosecution, the ICC and local or traditional practices are very mixed (United Nations, Office of the High Commissoner for Human Rights 2007). The other survey, conducted by researchers from the Berkeley–Tulane Initiative on Vulnerable Populations and the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), produced similar results: there are high levels of support for a traditional approach, but a majority of interviewees wanted the perpetrators of grave human rights violations to be held accountable (forthcoming publication).

Cultural attitudes also have an influence on views on truth commissions. In his report on the TRC in Sierra Leone, Tim Kelsall argues that, in the absence of strong ritual inducement, the public telling of the truth ‘lacks deep roots in the local cultures’ of that country (Kelsall 2005: 363). A similar situation exists in Burundi and Rwanda.

3.4.2. How to merge different strategies?

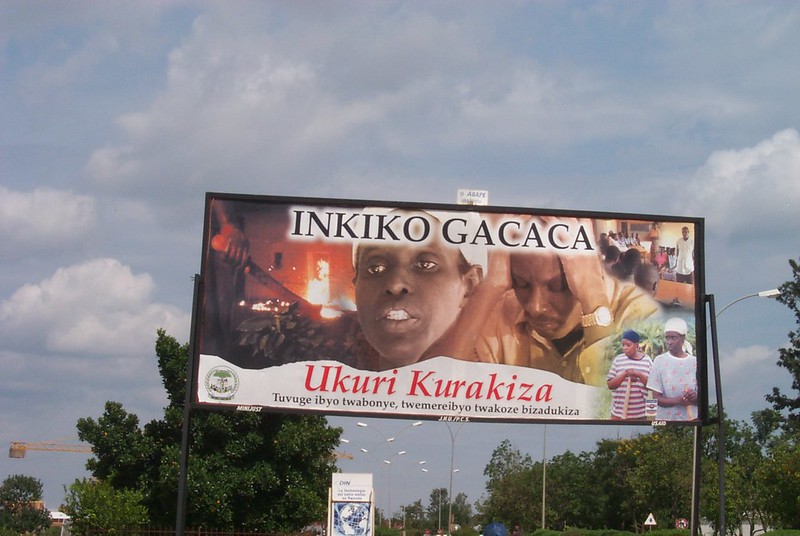

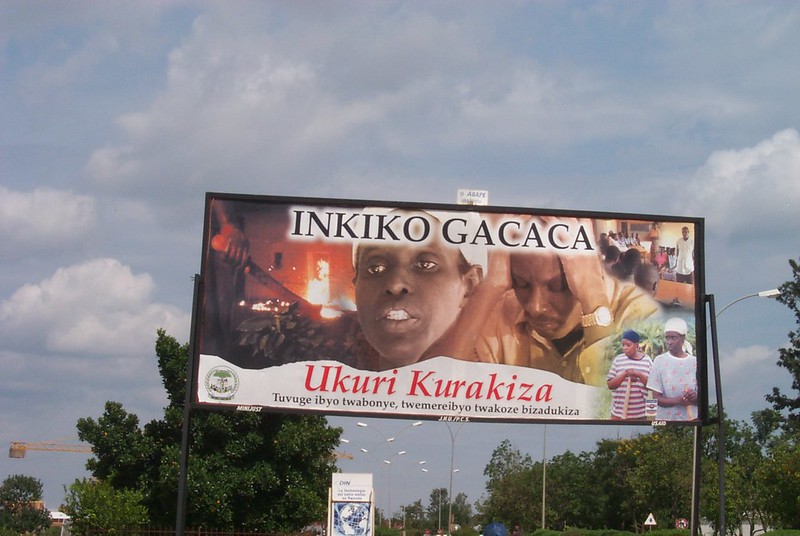

Most of the countries studied as part of this project combine traditional justice and reconciliation instruments with other strategies for dealing with the legacy of civil war and genocide: in Mozambique with an amnesty act; in northern Uganda with an amnesty act and the intervention of the ICC; in Rwanda with the Arusha court, national tribunals and Gacaca meetings; in Sierra Leone with a special court and a truth commission. (Burundi is an exception to that rule. Its Ubushingantahe is neither formally nor informally involved in the actual programming of transitional justice.) How do these strategies interrelate? How can interpersonal and community-based practices live side by side with state-organized and/or internationally sponsored forms of retributive justice and truth telling?

(This is not a problem that is unique for Third World countries in general, or African post-conflict societies in particular. The search in Western Europe and North America for a justice mechanism that can complement a purely punitive approach has generated renewed interest in traditional non-state systems of dealing with crime. In Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States traditional justice systems belong to the aboriginal heritage and have recently been revived. Interest in restorative justice programmes is on the rise in other Western countries but this is based more on progressive contemporary philosophies of justice than on a forgotten local tradition. One example is victim–offender reconciliation programmes. That formula has been used predominantly to handle fairly minor crimes, although initiatives in conflict contexts such as Northern Ireland have tried to extend the concept.)

Our case studies report a considerable diversity in the reception of traditional mechanisms. There is a clear aversion in most political circles in Burundi. Mozambique is a case of passive tolerance. It is, however, useful to remember that in such contexts certain dangers may emerge. Victor Igreja and Beatrice Dias-Lambranca write that ‘magamba and other similar post-war phenomena run the risk of being wrongly used by the national political elites. For instance, political elites can use the success of magamba spirits and healers as arguments to justify their option for post-war amnesties, impunity and silence’. Official recognition of the value of reconciliation and cleansing rituals has been the reaction in Sierra Leone. But their incorporation into the workings of the TRC has been rather weak. The June 2007 Juba agreement between the Ugandan Government and the LRA plans full integration of the mato oput ceremonies into the national policy on the war crimes of the past. Rwanda is the only country where a local accountability instrument has been wholly part of the official policy. This chapter has already mentioned the problems that arise in such situation.

Source: IDEA