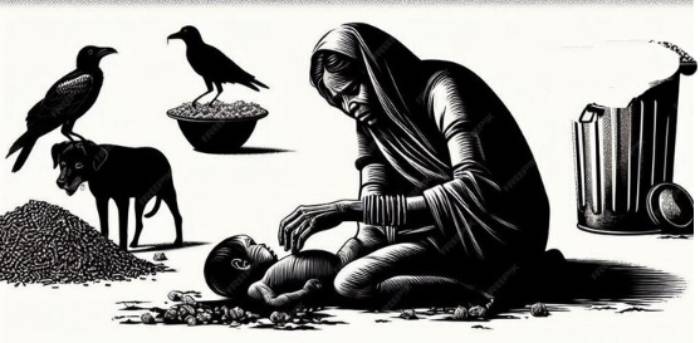

The Time of Famine

By Abdallah Rizq Abu Simaza

“No electricity.” And before that, “No gas.” Simple words, yet they reveal a deeper crisis—the fuel crisis, whose severity grows alongside the rising cost of coal and firewood. And with it, famine silently looms, threatening, according to United Nations reports, nearly 25 million Sudanese.

I forgot to add: “No money.” No jobs, no source of income, and the basics have become an unattainable luxury. The prices of essential goods—which are becoming scarce in the markets—continue to rise relentlessly, far beyond the reach of the average citizen. Many have been forced to sell their used household appliances for meager sums in a desperate attempt to afford the bare necessities: flour, bread, sugar, lentils, onions, oil... the list is long, and the suffering is far too deep to be summarized.

“No gasoline.” Another livelihood blocked for many families. Rickshaws have almost entirely stopped operating due to fuel shortages and skyrocketing prices (ranging between 30,000 and 40,000 Sudanese pounds per gallon). It’s now a familiar sight to see a family pushing a rickshaw loaded with a water tank to fill it from the nearest well. The water is often salty or bitter but free—the freshwater wells are out of reach, both geographically and financially.

But heaven’s mercy hasn’t completely disappeared. Recent heavy rains in Al-Wadi Al-Akhdar have somewhat alleviated the severe water crisis, providing some families with their basic needs, even if only temporarily.

Families without financial support from abroad are living through their worst days. Shopkeepers refuse to give credit, knowing that debtors are unlikely to repay anytime soon. Even journalist Abdul Wahab Musa, who resorted to selling vegetables in the City of Journalists at the beginning of the war, had to stop due to the citizens’ dwindling purchasing power.

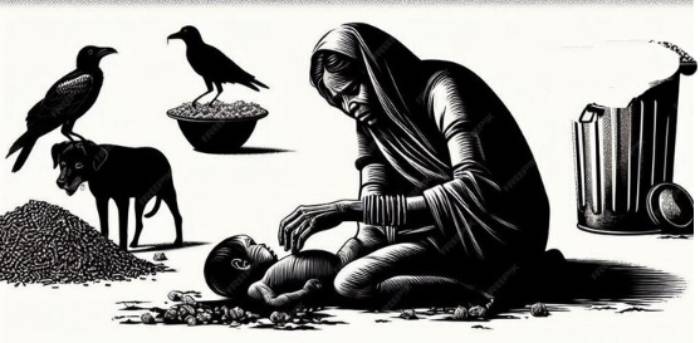

In these harsh circumstances, families are turning to solutions that seem almost miraculous. Many have started selling their wooden furniture, even dismantling the thatched huts that once served as shelter and shade, to use as fuel for cooking whatever food is available—beans or lentils.

At the “Last Station” market, the narrow alleys are crowded with broken furniture: wardrobes, tables, beds, and even bookshelves that once symbolized culture. One of the saddest days of my life was when I had to burn my private library to feed my family. Shakespeare, Abdullah Al-Sheikh, Mustafa Sayyid Ahmed… all consumed by the flames on a day I will never forget.

And yet, the question that chokes everyone remains: “What will we eat?”

It’s a daily tragedy that repeats itself, and merciless hunger spares no one. I remember “Mr. K,” whose decomposed body was found days after he had died, alone in his harsh isolation. Hunger left him no chance of survival, acting as the silent killer that emerges only in the quiet.

I told Dr. Anwar Shambal, a professor of journalism at the University of El Fasher:

“When the war ends, we should erect a statue of the lentil at Sudan’s celestial gate. The lentil, a feminine figure, stood by us when fava beans abandoned us.”

Perhaps, in a fairer world, the lentil deserves a place on Sudan’s flag, just as the maple leaf adorns Canada’s.