Global Crises: Sudan Tops the Rankings

Khalid Massa

In a country like Sudan, where "crisis" is an open book visible to anyone stepping outside their door or even waiting for crises to arrive uninvited into their homes—be it economic, health, or security crises—it is perplexing that all warnings about these issues are often dismissed and politicized, creating a climate of extreme polarization.

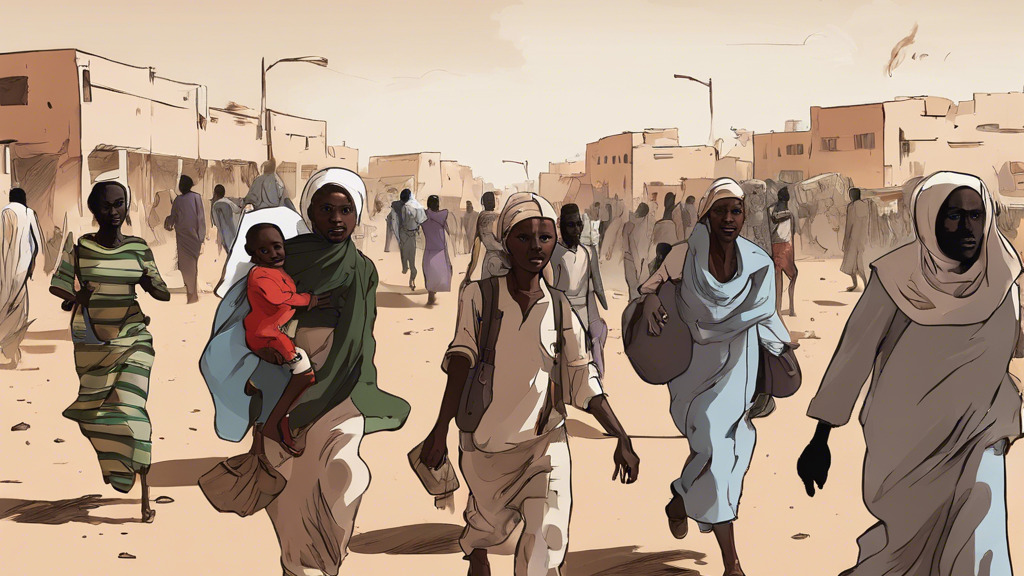

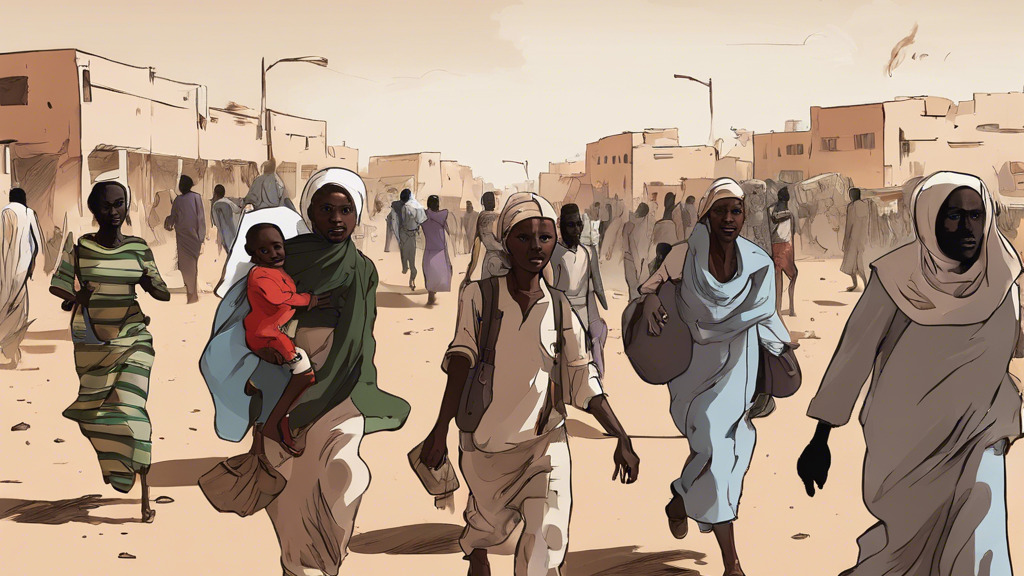

Everyone is quick to suspect the worst when alarm bells ring, especially as voices warn that the tree of crises leans heavily toward Sudan. Once described as the "breadbasket of the world" due to its Nile waters and fertile soil, Sudan now stands on the brink of famine, exacerbated by a war raging for nearly two years. Approximately 25 million Sudanese face acute food insecurity, while the rest struggle to secure sustenance amid severe hardship.

This denial is not unique to Sudan; it is a common response among those unable to confront their peoples challenges with responsibility and courage. This global phenomenon led to the creation of the International Crisis Group (ICG) in 1995, an independent and neutral organization tasked with awakening global awareness to prevent crises like those in Somalia, Rwanda, and Bosnia, which cost millions of lives due to humanity’s earlier denial.

For the second consecutive year, Sudan has been prominently featured in the ICG’s annual report, competing with other crisis-stricken nations for a front-row seat. This report is a vital, independent resource for governments, international organizations, and UN agencies. Backed by global standards and crisis measurement indicators, the report starkly contrasts with the ignorance and denial prevailing among Sudanese citizens enduring the aftermath of the April war.

This denial, however, must not become another weapon of war, offering no solutions while ignoring the alarm bells sounded by such classifications.

Sudan’s position at the top of the ICG’s global crisis rankings demands a more rational response than dismissing it through shallow definitions of "sovereignty" and colonialism. The Sudanese people, over 80% of whom have lost their livelihoods due to the war, face a collapsed currency, triple-digit inflation, and a health system ravaged by 11 billion in damages, according to the federal health minister. Entire hospitals have ceased functioning, educational and essential services like electricity and water are disrupted, and 230,000 children and pregnant women are on the brink of starvation. The war has devastated agriculture, reduced planted areas, depleted crop reserves, and blocked vital supply routes.

Viewing such crises through a political lens—often influenced by attitudes toward the war—gravely harms civilian victims. This is especially concerning given the international community’s moral responsibility toward populations affected by crises. In Sudan, where decision-making institutions lack the tools to assess crises and measure their impact, and where local organizations struggle with neutrality and independence, the ICGs classification becomes indispensable and warrants sensitive engagement.

One of the ICG’s key responsibilities is advocating for a global system based on laws rather than force, particularly by influencing UN decisions to implement the "Responsibility to Protect" standard. This standard emphasizes protecting civilians during wars, such as the ongoing conflict in Sudan.

The prolonged and expanding war means updated figures from organizations like the UNHCR, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and UNICEF. Sudan’s name is unlikely to budge from the top of the ICG’s crisis rankings, especially given its fragile and unstable region, where neighboring countries like Ethiopia contend for similar rankings.

The immediate positive action required is for the ICGs rankings and accompanying reports to be a priority for the Supreme Committee announced by the Sovereignty Council to collaborate with the UN and its agencies. This could help Sudan move from a state of denial toward solutions that might salvage what remains of the war’s victims.

The international community, with all its organizations and structures, must abandon its sluggish and bureaucratic response to crises. It must recognize that humanity cannot endure another museum of victims and move beyond self-serving decision-making processes that have historically skewed crisis assessments. If not, the tireless efforts of crisis experts to analyze, predict, and propose solutions will be wasted, relegated to the international community’s trash bin.